Summarize and humanize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in EnglishWhen Liverpool travelled to Manchester City for a 1-1 draw in November last season, the matchday programme cover depicted an imagined scene from the contest. Jeremy Doku was dribbling down the left, with Bernardo Silva and Josko Gvardiol for company. That sounds about right.But there was also something about the scene that didn’t look right. Liverpool captain Virgil van Dijk had slid in to tackle Doku, but had completely missed the ball.By and large, that doesn’t happen. In arguably his peak season, 2018-19, Van Dijk played 38 games, made 38 tackles, and not once did an opponent dribble past him. There have always been formidable defenders, of course, but in this enlightened era of analytics, this was the first time a centre-back boasted a statistically verified reputation for being impossible to beat.Van Dijk isn’t quite putting up those numbers these days. This season, according to Opta, he’s attempted 34 tackles and won ‘only’ 16. But despite having missed the majority of 2020-21 through injury, and despite question marks about his mobility upon his return, Van Dijk remains the Premier League’s most respected centre-back. He turns 34 this summer, but few doubt that Liverpool are right to give him a new two-year contract. So why is he beaten so rarely?

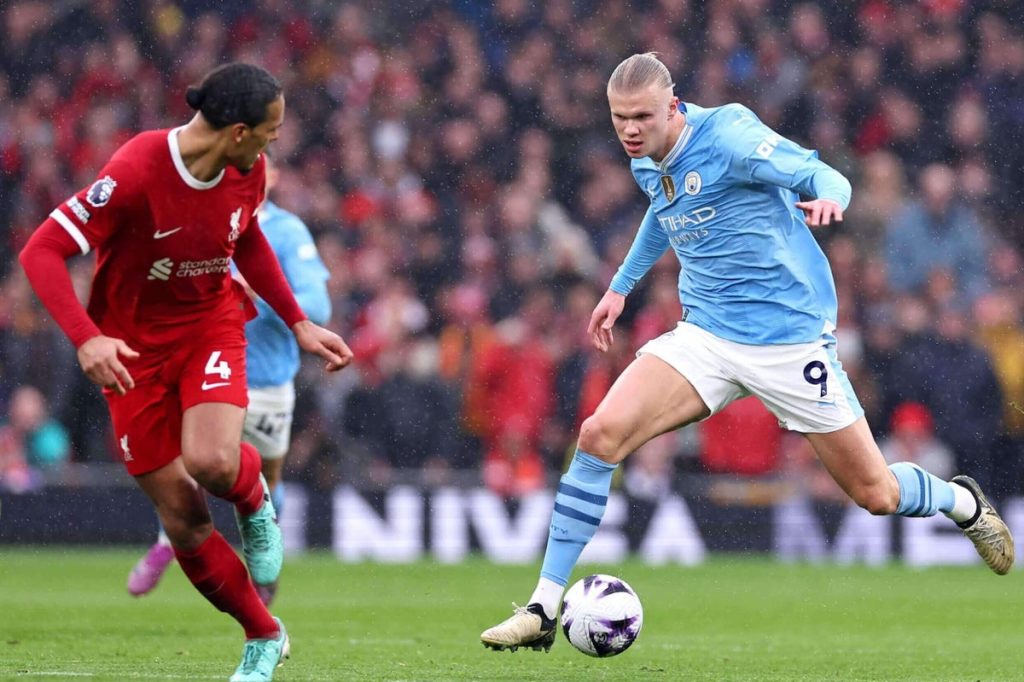

Van Dijk in an unusual situation on a programme cover from November 2023 (Manchester City FC)Actually, let’s first look at the opposite, and look at what happens when Van Dijk is beaten by an opponent, because the interesting thing about watching those clips is how regularly the Dutchman gets back and atones for his own initial error, usually by using his speed.In this incident, he moves across to tackle Brentford’s Bryan Mbeumo, gets beaten but, without too much bother, simply runs back and wins the ball. Here’s a similar incident a couple of years ago against Aston Villa, where Van Dijk is beaten by his former team-mate Philippe Coutinho, and is seemingly out of the game. But once again, Van Dijk has the speed to catch up and get goal side, uses his strength to win the ball, and to add insult to injury, he ends up being the one dribbling up the pitch. Van Dijk has always been about deceptive pace, as Sergio Aguero once acknowledged when saying the defender was his toughest-ever opponent. “We all know he’s one of the best. He’s strong, tall, athletic,” Aguero said. “He maybe doesn’t look that fast, but he gets to everything with those long legs. Two steps from him are the same as 50 for me.”Overall, the occasions when Van Dijk has been dribbled past are less damning than you might expect. The attempts that are statistically recorded as him missing tackles are, in reality, often an opponent reaching a loose ball more quickly than him, rather than him actually being dribbled past.On other occasions, Van Dijk is content for opponents to dribble back past him away from goal — or they go past him but are being shepherded into a wide area, from where they can only attempt a weak cross or shot. More than most other things on a football pitch, there’s slightly more nuance and opinion involved in whether something is truly an ‘unsuccessful’ tackle.Here, Bukayo Saka is credited with dribbling past Van Dijk — and technically he does, and Van Dijk misses the tackle. But ultimately Saka ends up slicing a cross over, under pressure from Van Dijk, so you’d still consider that Liverpool’s captain won that duel. There are only two obvious examples from recent Premier League seasons of Van Dijk being directly dribbled past and Liverpool conceding a goal. On both occasions, it seemed like he lost his footing more than anything else. There was this failure to stop Ivan Perisic setting up a Harry Kane volley at Anfield… And also a stumble away at Bournemouth for a Philip Billing goal. But, back to the question — why is Van Dijk dribbled past so rarely?The obvious answer is because he generally doesn’t need to make tackles. Very good players rarely have to. Xabi Alonso once described tackling as a ‘last resort’; Paolo Maldini said that if he was forced to make a tackle, he’d already made a mistake. That’s probably not quite true, particularly when covering for error-prone team-mates, and Liverpool’s full-backs haven’t always been the most defensively reliable.Van Dijk’s positional sense is excellent and when opponents receive the ball with their back to goal, he gets tight and prevents them turning. He’s almost never beaten in that situation, when a player tries to spin him — but he also doesn’t get too tight too early.Here’s a good example — Van Dijk gives himself space in case Dejan Kulusevski wants to run in behind onto a through ball. But as soon as the ball is played into his feet, Van Dijk is all over him. Van Dijk is a Rolls-Royce of a defender — physically intimidating but not overwhelmingly reliant on his strength.But when he does use his strength, he does so in a subtle way. Here’s a rare example of a striker taking the ball on the turn and going past him. But Van Dijk, in a position where the referee can’t quite see, uses his physique to barge Leicester’s Patson Daka to the ground, before gesturing for him to get up. Is it a foul? Maybe. But Van Dijk knows how much he can get away with, and his reputation as a calm, clean defender helps on the rare occasions he’s a little underhand. In situations when the striker is facing the goal, Van Dijk’s approach is very specific. More so than other defenders, he backs off. Sometimes this seems somewhat extreme, as he allows opponents to carry the ball closer to goal than you’d expect. But they rarely get an entirely free shot at goal and, more relevantly in terms of the tackling numbers, they never have much opportunity to actually go past Van Dijk.A good example is Erling Haaland’s individual battle against him last season, when Liverpool had every other defender out of the game, and Haaland had absolutely no support. It’s rare to see a situation like this in football, which is what made it so memorable.The interesting thing was not merely that Van Dijk ‘backed off’, because this body position here probably isn’t the correct description for that. Here, Van Dijk actually turns his back on Haaland. He would rather be facing his own goal than caught ‘square on’.Who ‘won’ this battle? Statistically, no one, because Haaland didn’t end up attempting to go past Van Dijk, and Van Dijk didn’t make a tackle. Haaland got a shot away — and it was on target — but it was under pressure from Van Dijk, and directed straight at the goalkeeper.That’s a nice summary of Van Dijk’s defensive play.Here’s another example, against Nottingham Forest’s Anthony Elanga. At no point does Van Dijk ever really engage with Elanga, or actually do anything at all. He just waits, forces the Swede to make a decision, and Elanga almost ends up running into him. Granted, his languid approach sometimes looks strange, although it’s probably been more damning in a different type of situation. For example, when Saka opened the scoring at the Emirates in a 2-2 draw earlier this season, having cut inside Andrew Robertson, Van Dijk should have got back quicker into position to cover for the Scot.Van Dijk is also simply very good at tackling, and a YouTube video with the F2 Freestylers is particularly revealing in terms of his tactics.“You should never be like this (square on), that makes it easier for the striker,” he says. “Because you can’t move easily. So you go into this position (side on), and pick a side where you want the striker to go, so you put a trap. You try to know which side is best to go, so onto their weaker foot.“I try to look at their eyes, because if someone in front of you is very technical and doing all the tricks, you might think, ‘What’s going on here?’. But you can see in the body language, and I like to look at players’ eyes. You hold off, because in my case I’ll have (team-mates) running back, and then I just try to win it in a clean way.”The other noticeable thing is that attackers seem aware of Van Dijk’s aura. It feels like opposition players, particularly those who probably don’t believe they have the speed to go past Van Dijk, attempt an ambitious flick, almost as if they know they’ll probably lose the duel, so need to try something special. It rarely comes off. Van Dijk doesn’t dive in, and simply stands his ground.

Van Dijk rarely has to dive in on opponents (Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images)But defending is inherently reactive, and part of the reason Van Dijk makes so few tackles is that some strikers simply play towards the other side of the pitch. Ibrahima Konate is having a fine season — and is also good at winning tackles himself — but Liverpool’s right-sided centre-back is generally considered the weaker of the two.There’s also the fact that Trent Alexander-Arnold isn’t the most formidable of defenders and sometimes ends up in central positions in possession, unable to cover his normal zone. Therefore, there’s more incentive to play from the left of the attack, with Manchester United’s Rasmus Hojlund particularly keen to do so in the 2-2 draw at Anfield earlier this season.But can we statistically show that strikers avoid Van Dijk? Here’s a map plotting Van Dijk’s usual defensive zone with the average touches of centre-forwards playing against Liverpool this season. Their touches extend a little further to the left, towards the other channel, and the average position is just out of reach from Van Dijk’s usual zones. But there isn’t that much in it.How about looking at things individually? Below are heat maps of the strikers who have played against Liverpool so far this season, broken down into two groups of 16.This shows why averaging things out is a little problematic. Mbeumo was considered Brentford’s most advanced player in their 2-0 loss to Liverpool, but he was playing in a 4-4-2 and asked to work the right channel with Yoane Wissa focusing on the left channel, so this somewhat skews the data.The same is true of Georginio Rutter, who partnered Danny Welbeck in Brighton’s 2-1 loss at Anfield, with the two playing on different sides of the pitch. Also, Raul Jimenez’s extreme right-sided positioning in Fulham’s 2-2 draw at Anfield can be attributed to Robertson’s red card, and Arne Slot’s decision to move Joe Gomez into an unfamiliar left-back role, so Jimenez decided to play up against him.But there’s evidence from elsewhere that strikers tend to favour the other side of the pitch. Look at the above graphic, and it seems that ‘proper’ No 9s like Liam Delap, Evanilson, Ollie Watkins, Eddie Nketiah, Nicolas Jackson and Daka all position themselves towards the opposite side.Here are the next 16 games…Again, it feels like we can break things down into two different types of striker. Proper No 9s — Daka, Chris Wood, Delap again, Beto (although only in the first of the two Merseyside derbies), Watkins, Callum Wilson and Rodrigo Muniz — tend to play towards the opposite side.The players who drift to the right are, in general, not strictly speaking centre-forwards. Dango Ouattara, Jean-Ricner Bellegarde and Jarrod Bowen are generally considered midfielders, or wingers. They tend to drift into deeper and wider positions, or alternate with team-mates, so they’re not truly playing up against Van Dijk.Fulham’s approach in their 3-2 victory over Liverpool earlier this month was a good example. Muniz played up against Konate, while Andreas Pereira in the No 10 role played in the right channel. As it happens, Van Dijk did get bypassed for one of the goals, thanks to Muniz’s remarkable aerial control and finish. But Fulham’s game plan was about speed in behind to the left and linking play to the right.It does seem that opponents don’t take on Van Dijk, either by coming short, or by playing towards the opposite side.So while the old Maldini quote about how he shouldn’t need to make tackles is a decent rule, maybe top centre-backs like him underestimate the extent to which players simply don’t try to beat them. Strikers get spooked by the aura of world-class defenders, and avoid them altogether.And if there’s one current defender you want to avoid, it’s Van Dijk.(Top photo: Virgil van Dijk defends against Erling Haaland. Robbie Jay Barratt – AMA/Getty Images))