Summarize and humanize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in English

American movies overflow with arrested-development cases. (There’s something very American about that.) Yet it’s not every day that you see an engaging indie comedy about “adulting” — that is, characters of a certain age who are still sealed inside the youth bubble, to the point that they regard conventional grown-up activities like holding down a job or taking care of another person as beyond-their-pay-grade endeavors.

The smart and fluky “Sacramento” is that kind of movie. It’s been called a road comedy, and technically it is, if you count as a road comedy a film in which the two main characters are old friends who may no longer even like each other, who climb into a vintage gold Chrysler Imperial — the car they shared in their youth — and drive from L.A. to Sacramento, a trip that takes all of six hours (and occupies about 25 minutes of the movie).

Why are they going there? In what feels like it could be a mumblecore gloss on “A Real Pain” (though maybe, given the shift in generational temperament, we should revive and rechristen that now-ancient genre by calling it chattercore), Glenn (Michael Cera), who resides in L.A., is the nerdish conservative settled-down one, and Rickey (Michael Angarano), his oldest and closest buddy, who shows up out of nowhere, is the reckless dude who has turned his refusal to grow up into an increasingly frazzled and even crazy state of being.

For starters, he’s a pathological liar. Rickey convinces Glenn to go on the trip by explaining that his father died a month ago, and that he wants to go to Sacramento to scatter his dad’s ashes in the ocean. There are just a couple of problems with that story. Sacramento isn’t near the ocean. And when they stop at a convenience store, Rickey quickly empties out a canister of tennis balls and fills it with dirt — the “ashes” of his father.

So the entire trip is based on a false pretense. But Glenn, the upright one, isn’t coming clean either. He hasn’t even told Rickey that his wife, Rosie, played by a no-nonsense Kristen Stewart, is eight months pregnant. (Rickey, spotting the sides of a crib in the backyard, figured it out.) And while Rosie couldn’t be cooler about it, Glenn is freaking out. Sure, that’s what’s fathers-to-be are supposed to do (and maybe always have done), but in “Sacramento” the point is that the prospect of becoming a daddy sounds, to Glenn, like the adulting Olympics. He’s a nice millennial husband, doting and attentive, but where this is all heading isn’t real to him. And it’s giving him a repressed nervous breakdown.

Then the thing he’s been fearing comes true: He loses his job (it sounds like he works for a tech company, one that’s having major layoffs). Welcome to adulting 2.0.

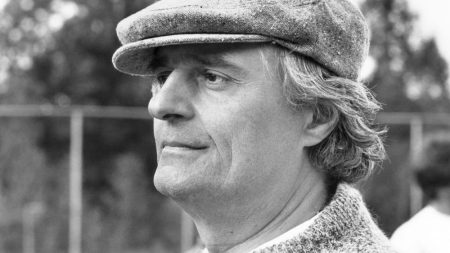

In addition to giving a spiky, compelling performance as Rickey, the film’s equivalent of the Kieran Culkin fast-talking-bearded-charmer-with-sociopathic-tendencies in “A Real Pain,” Michael Angarano directed and co-wrote “Saramento.” And he proves to be a confident and vivacious filmmaker, though in an engagingly scruffy and almost random way. He doesn’t concoct fatally cute road-movie episodes (thank God). He wants to show us who these two dudes are — their mix of oldest-friend-in-the-world intimacy, fermenting-in-age skepticism, and sheer irresponsibility. Once they reach Sacramento, they stop at a bar and connect with a couple of women (AJ Mendez and Iman Karram) who own and operate a fighting gym, and we get a taste of the way that these two used to tomcat around, probably competing for the same women, all to fuel their competitive camaraderie.

But that’s all just bro nostalgia. Why are they here now? Because Rickey, it turns out, has a baby of his own, and hasn’t begun to own up to being a father. He bailed on the kid’s mother, Tallie (Maya Erskine), and isn’t even sure she wants him around. (That he has rights doesn’t occur to him.) This is the adulting apocalypse. And to get through it, what Rickey and Glenn need to do is to claw right down into each other’s misfit selves.

Angarano has the showpiece role, but it’s Cera who proves himself, more than ever, to be a major actor. At first, when you see him in his patchy beard, you think he’s just playing some older version of the Michael Cera of old. But he has a less derisive, more rooted presence now, and he’s doing something more daring. He creates a character rippled with pain and lunging for happiness. Michael Cera has been knocking around TV and the indie world for years now, but if Hollywood still wants to make real movies there could be a major place for him.