Avian Flu Variant in Cattle Sparks Concerns About Mammalian Adaptation

A new strain of avian influenza (H5N1) detected in Nevada dairy cattle has raised scientific concerns due to a genetic mutation that may help the virus replicate more efficiently in mammals, including humans. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports this variant, known as D1.1, could pose a heightened threat to farmworkers and others with direct animal exposure. While the CDC maintains that the overall public risk remains low, a recent case involving a Nevada dairy worker—marking the state’s first human infection—highlights the need for vigilance. The worker exhibited conjunctivitis (pink eye), a symptom previously seen in other mild H5N1 cases.

D1.1: A Hybrid Virus Linked to Severe Human Cases

The D1.1 variant represents a significant shift in the H5N1 landscape. Unlike the more common B3.13 “cattle clade,” which has caused mostly mild infections in U.S. dairy herds, D1.1 is linked to severe human illnesses. It emerged from a genetic “shift,” blending segments from a highly pathogenic Asian H5N1 strain and a milder North American flu virus. First identified in wild birds in late 2022, D1.1 became dominant among North American avian populations by late 2023. Its jump to cattle in Nevada—sparked by suspected contact with wild birds or their droppings—marks a worrying expansion of its reach.

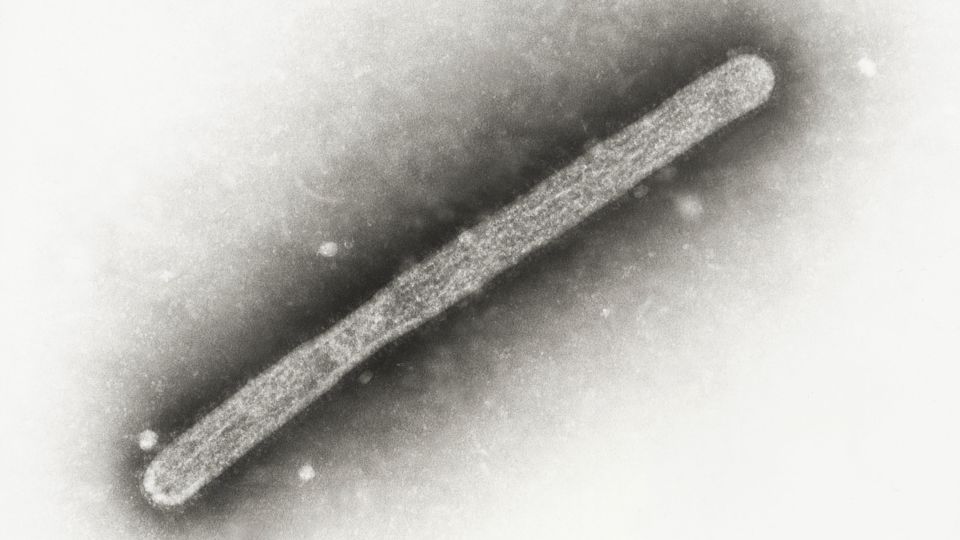

Mutations Matter: How D1.1 Evolved to Threaten Humans

Viruses mutate through two primary pathways: drift (small genetic tweaks) and shift (major genome swaps). D1.1 arose from a shift, combining parts of deadly H5N1 with a low-risk North American flu strain. This hybrid carries a mutation in its hemagglutinin (H) protein, a structure that helps the virus invade cells. Researchers believe this change enhances D1.1’s ability to infect mammals. While similar mutations haven’t appeared in other D1.1-infected birds, scientists speculate that intermediary animals like cats or foxes might have introduced the strain to cattle, allowing it to adapt further.

Severe Human Infections: A Pattern Emerges

D1.1 has already caused alarming human cases. In late 2023, poultry farm workers in Washington and a teenager in Canada contracted the strain. The Canadian patient suffered multi-organ failure but survived, while a Louisiana individual exposed to backyard birds later died. Genetic analysis revealed additional mutations in their viruses, suggesting D1.1 may adapt more easily to humans. Researchers are investigating why this strain triggers severe illness. One theory centers on its neuraminidase (N) protein, which differs markedly from seasonal flu strains, potentially evading preexisting immunity.

The H-N Tango: A Clue to D1.1’s Danger

The interaction between H and N proteins is critical. While H helps the virus enter cells, N aids its escape after replication. Dr. Scott Hensley, a microbiologist, hypothesizes that D1.1’s N segment might allow its H protein to mutate without losing efficiency—a rare balance that could make it more adept at infecting humans. Meanwhile, Dr. Louise Moncla notes that D1.1’s distinct N protein might bypass immune defenses shaped by seasonal flu exposure. Ongoing lab studies aim to unravel how these genetic quirks influence transmission and severity.

Unanswered Questions and the Path Forward

The Nevada outbreak underscores gaps in our understanding. How did D1.1 reach cattle despite being rare in birds? Can it spread between cows, or was this an isolated spillover? Health agencies urge precautions for high-risk groups, including protective gear for farmworkers and monitoring of backyard flocks. While current risk is low, D1.1’s rapid evolution highlights the need for genome surveillance and preparedness. As researchers race to decode this virus, the interconnectedness of animal and human health—and the unpredictability of zoonotic threats—remains clearer than ever.