A Curious Mind in the Autumn Leaves: Charles Henry Turner’s Revolutionary Bee Experiment

On a crisp autumn morning in 1908, biologist Charles Henry Turner transformed a St. Louis park into a living laboratory. Among the rustling pin oaks and magnolias of O’Fallon Park, Turner laid out a sugary feast—dishes of strawberry jam placed on picnic tables—to study honeybee behavior. Over days of meticulous observation, he noted that bees initially visited the jam at dawn, noon, and dusk. But when Turner altered the schedule, offering food only in the mornings, the insects adapted, returning solely at daybreak. This elegant experiment revealed something extraordinary: Bees could perceive time and adjust their habits to changing conditions. Turner’s work shattered assumptions about insect intelligence, positioning him as a visionary in a field that often dismissed such creatures as mindless automatons.

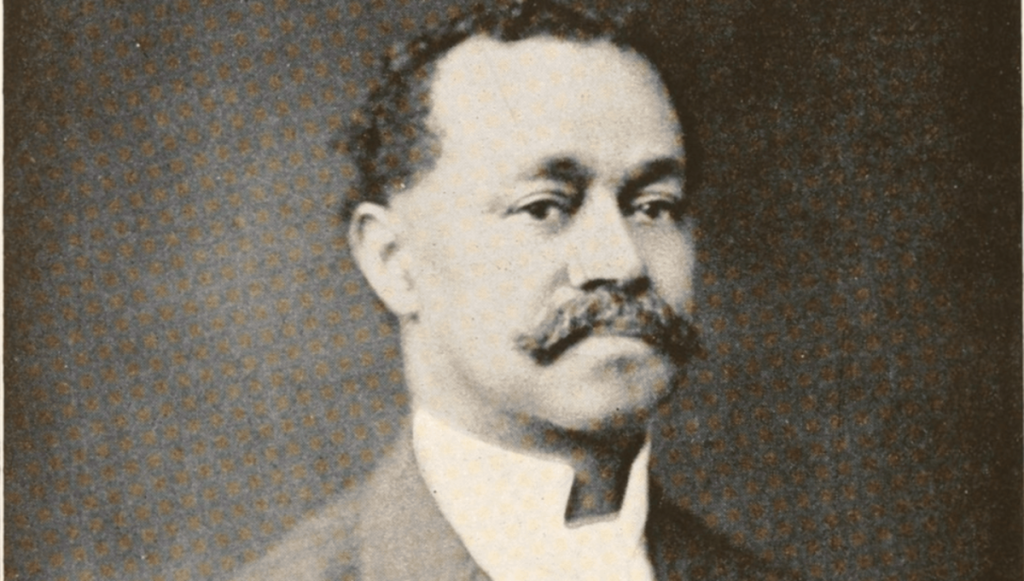

From Adversity to Academia: The Unlikely Journey of a Pioneering Scientist

Born in 1867 to a formerly enslaved mother and a church custodian father, Charles Henry Turner grew up in a segregated Cincinnati riddled with systemic racism. Despite the suffocating grip of Jim Crow laws—which barred Black Americans from equal education, housing, and voting—Turner’s brilliance shone early. He devoured books on biology, cataloged insects, and graduated as valedictorian of his all-Black high school. His academic journey continued against the odds: He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Cincinnati and became the first African American to receive a PhD in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1907. Yet even with groundbreaking research on ant behavior, Turner faced closed doors. Denied university positions, he spent his career teaching at Sumner High School, a Black public school in St. Louis. There, without labs or funding, he conducted pioneering experiments that redefined entomology.

Seeing the World Through Bees’ Eyes: Unlocking Insect Intelligence

Turner’s fascination with insect cognition led him to ask bold questions. Could bees recognize colors? Did they rely on scent alone to find flowers? To find out, he hammered wooden rods into the park lawn, topping some with red disks dipped in honey and others with unscented blue disks. Bees flocked to the red “flowers,” ignoring the blue ones—a finding that suggested they used visual cues, not just smell, from a distance. Though debated at the time, modern science later confirmed that bees detect contrasts in light and dark (achromatic stimuli), supporting Turner’s conclusions. His work challenged the era’s dogma, proving that insects like bees, wasps, and ants possessed memory, learning ability, and even problem-solving skills. “Insects are not machines,” Turner argued, offering a radical view of their inner lives.

A Teacher’s Legacy: Science, Race, and the Fight for Equity

Turner’s impact extended far beyond his experiments. At Sumner High, he inspired generations of Black students in science while advocating for broader educational reform. In a 1902 essay, he rejected the idea that vocational training alone could uplift African Americans. Instead, he demanded access to comprehensive education for all: “The highest education [is] the birthright of every child,” he wrote. His vision clashed with the era’s prejudices, yet he persisted, blending rigorous research with activism. Despite earning acclaim for his 71 published papers—including a historic 1910 Science article, a first for a Black scientist—Turner remained sidelined by white academia. His meager high school salary forced him to juggle teaching with research, often funding experiments out of pocket.

Defying Barriers: The Cost of Being a Black Pioneer

Turner’s story is inseparable from the racism that shaped his career. The University of Chicago refused to hire him. Tuskegee Institute, led by Booker T. Washington, couldn’t afford his position. Even his $1,080 annual salary (about $34,300 today) at Sumner High underscored the economic inequities of the time. Yet Turner’s resilience never wavered. He transformed park benches into labs, involved students in fieldwork, and published prolifically. His work on spider web building, cockroach learning, and ant navigation laid foundations for modern animal behavior studies. Tragically, his life was cut short at 56 by heart failure in 1923. He left behind a scientific legacy—but no university chair, no endowed lab, and little public recognition.

The Forgotten Father of Insect Cognition: Why Turner Matters Today

A century later, Turner’s insights resonate powerfully. His discoveries about bees’ time perception and visual learning foreshadowed today’s research on pollinator behavior, critical to addressing colony collapse and biodiversity loss. Entomologists still cite his papers, validating his methods and conclusions. Beyond science, Turner’s life embodies a fight for equity—a reminder of how racism has excluded Black voices from academia. Recent efforts to honor him, like naming a University of Chicago scholarship in his honor, hint at a long-overdue reckoning. As we grapple with climate change and insect decline, Turner’s work underscores a lesson he championed: Even the smallest creatures have much to teach us, and brilliance can flourish in the most unlikely places.

Charles Henry Turner’s story is more than a footnote in history. It’s a testament to curiosity, perseverance, and the transformative power of seeing the world—quite literally—through the eyes of a bee. In an era that dismissed both insects and Black intellectuals as unworthy of attention, Turner’s legacy buzzes on, urging us to look closer, think deeper, and recognize the quiet revolutionaries in our midst.