Summarize and humanize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in English

Tomasz Wolski’s documentary “The Big Chief,” which world premiered this week at Visions du Réel, follows the life of Soviet spy ringmaster Leopold Trepper. Variety speaks to Wolski about the film and debuts the trailer.

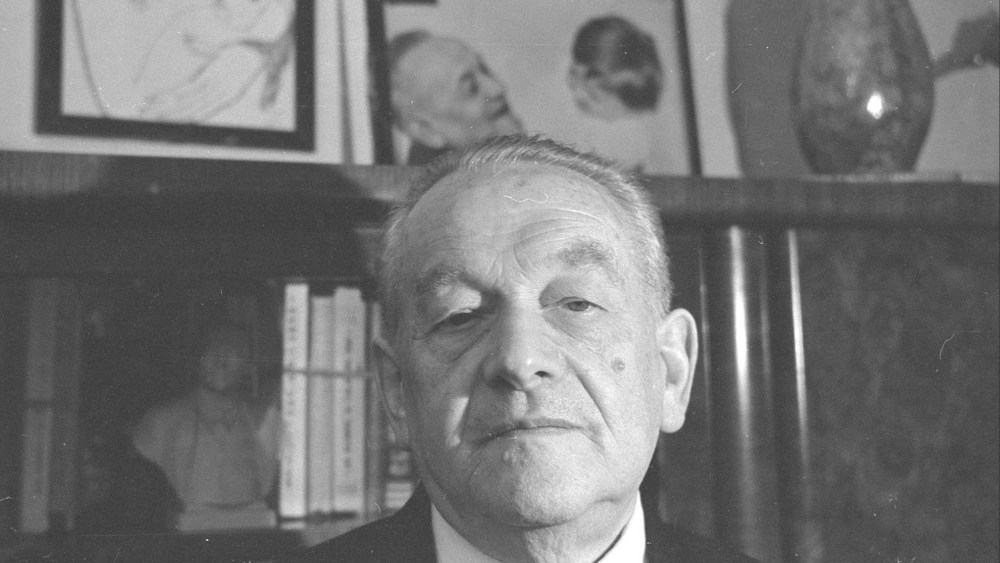

Trepper, a Polish-Jewish communist, ran a network of Soviet spies across Western Europe, named by the Germans as the Red Orchestra, from the mid-1930s until 1942, when he was captured by the Gestapo and then escaped. When he returned to Moscow after the war he fell out of favor and was imprisoned for 10 years. When he went back to Poland, he led the country’s Jewish community for some years, but was persecuted, and denied permission to emigrate to Israel.

In 2016, Wolski was researching another film, “An Ordinary Country,” in Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance, which holds documents and footage from the Nazi occupation through the decades of Soviet domination that followed.

“I was preparing a film about Poland through the eyes of secret service officers,” he says. “And, at some point, I found documents and film reels that were labelled Leopold Trepper.” He didn’t know who Trepper was, but was intrigued and delved into the files and footage.

There were more than 20 reels of film in this trove, showing interviews with Trepper conducted by a French crew, led by Jean-Pierre Elkabach, from the 1970s, and confiscated at the airport.

After Trepper was denied the right to move to Israel, and was put under round-the-clock surveillance, Elkabach and other supporters in France mounted a campaign to allow him to leave Poland. The head of the French intelligence service said that Trepper had collaborated with the Gestapo during the Nazi occupation of France and betrayed members of the Resistance to save his own skin. Trepper’s allies fought this in court and won, resulting in the French spy chief being removed.

However, there remains many enigmatic aspects to Trepper’s story, and for Wolski that is the point. “I made this film because I deeply believe you can’t be sure of what happened in the past,” he says. “I mean, we have problems finding out what’s going on around us now, so how do you get to the truth about some event that happened 80 years ago?”

He adds: “I don’t agree with journalists and historians who try to base their work on documents in the archives.”

One of the issues is that the competing intelligence agencies, including the French, Poles and the KGB, were all planting false information as part of their campaigns of disinformation during the Cold War.

One of the central issues is whether Trepper genuinely collaborated with the Gestapo after he was captured or, as he claimed later, he was feeding them false information and alerted the Soviets that the Red Orchestra had been compromised.

“I have a lot of doubts [about whether he genuinely betrayed the Allies], and I would even go as far as saying that I don’t believe that,” Wolski says. “But maybe, he just wanted to save his life. I don’t know. I mean the thing is that we cannot judge.”

He adds: “I don’t want to judge some of the decision made during the war, when their lives were threatened. We don’t know how we would behave in that situation. Completely different rules applied at that time, so it’s really hard to go there.”

One of the issues dealt with in the film was the antisemitism that was prevalent in Poland, especially after the 1968 student protests.

“Antisemitism is still present in Poland. I think we have a huge problem [with that], especially its impact in the past. A few years ago, when we had a different government, they clamped down on historians who were trying to find out the truth [about Polish antisemitism].”

He adds: “For some reason, we cannot accept that it happened. But, when your life is miserable, you have to find someone to blame, and the Jews are often [an easy target].”

He says: “This story is also about the Westerners who really wanted to help someone that was living [under a despotic state] in the East.”

Wolski himself had to deal with the divisive nature of politics in Poland. When he first submitted the project to the Polish Film Institute, under the previous conservative government, he was rejected. He had explained he wanted to be even handed but he was told that if he portrayed Trepper as a traitor he might get his funding. But, later, after a change in the expert in charge of the decision-making at the institute, he got his funding. At another funding body in Poland, the decision-maker questioned whether Trepper was actually Polish as he was born in an area that was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the time.

“The Big Chief” is produced by Anna Gawlita at Kijora Film. The co-producers are Polish Television TVP S.A., INA, Atoms & Void, KBF, and the Mazovia Institute of Culture. It is co-financed by the Polish Film Institute.